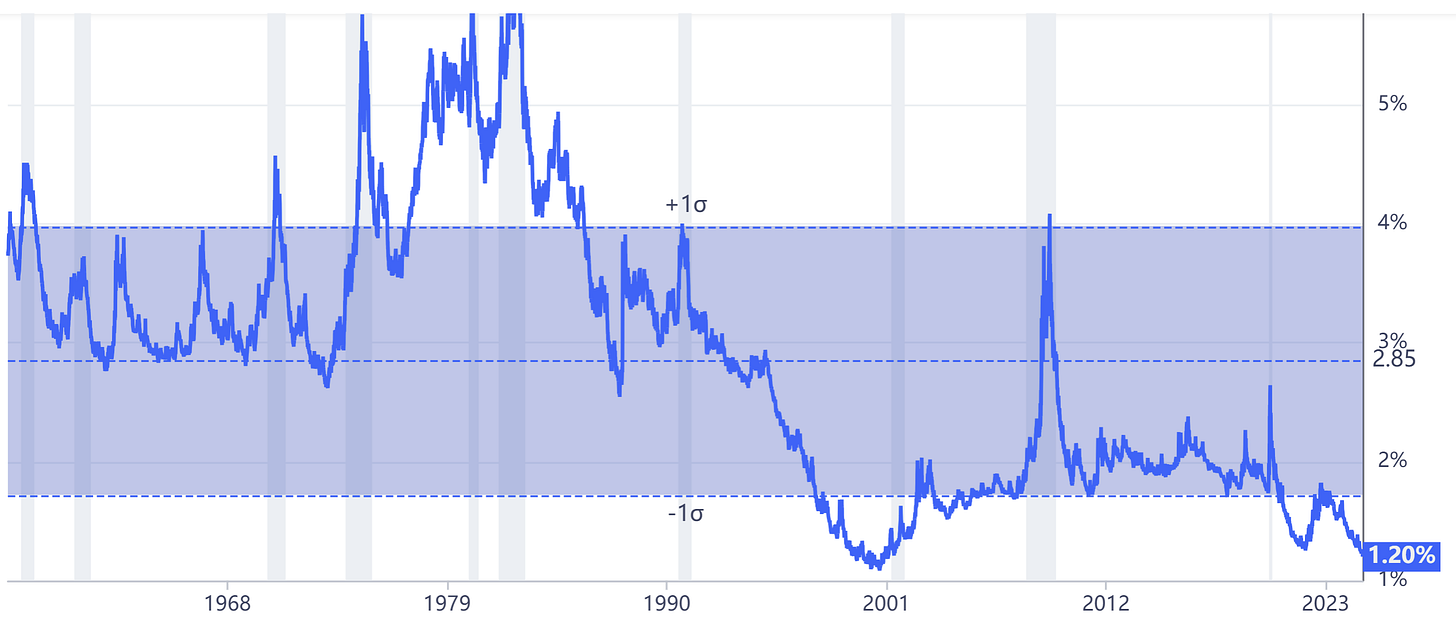

The current state of the high-flying stock marker reminds me of a time in my professional life when I was advising clients to avoid stocks. Then, as now, traditional valuation measures, such as dividend yield or the price/earnings ratio, were way out of line from their historical averages.

I was a quantitative analyst in the equity research department, so numbers were my thing. My clients were mostly tax-exempt institutions such as foundations or pension funds. I used statistical computer models to find opportunities for my clients, recommending individual companies or sectors of the stock market that I found to be both undervalued and poised for recovery.

I also studied the prospects of the stock market relative to the bond market, feeding into a process called asset allocation. Alarm bells were ringing, as my models were signaling that stocks were at historically dangerous levels. I made no bones about saying so to my clients.

One day, one of the salesmen on the equity trading desk pulled me aside. (With two exceptions, the sales force were all men.) “Do you know what you are being called on the desk?” he asked me. The desk was on a different floor from my office, and I seldom visited there. “No,” I said.

“Lenin!” he told me. “Not because you have a beard, but because you are un-American.” He went on to explain, “You have to understand that our job is to sell stocks, and you are telling people not to buy them — you can’t do that!” I was known as a contrarian, and some thought I was not a team player, but I knew which side of my bread the butter was on. I stopped telling people not to buy stocks. I told them instead, “Buy bonds.”

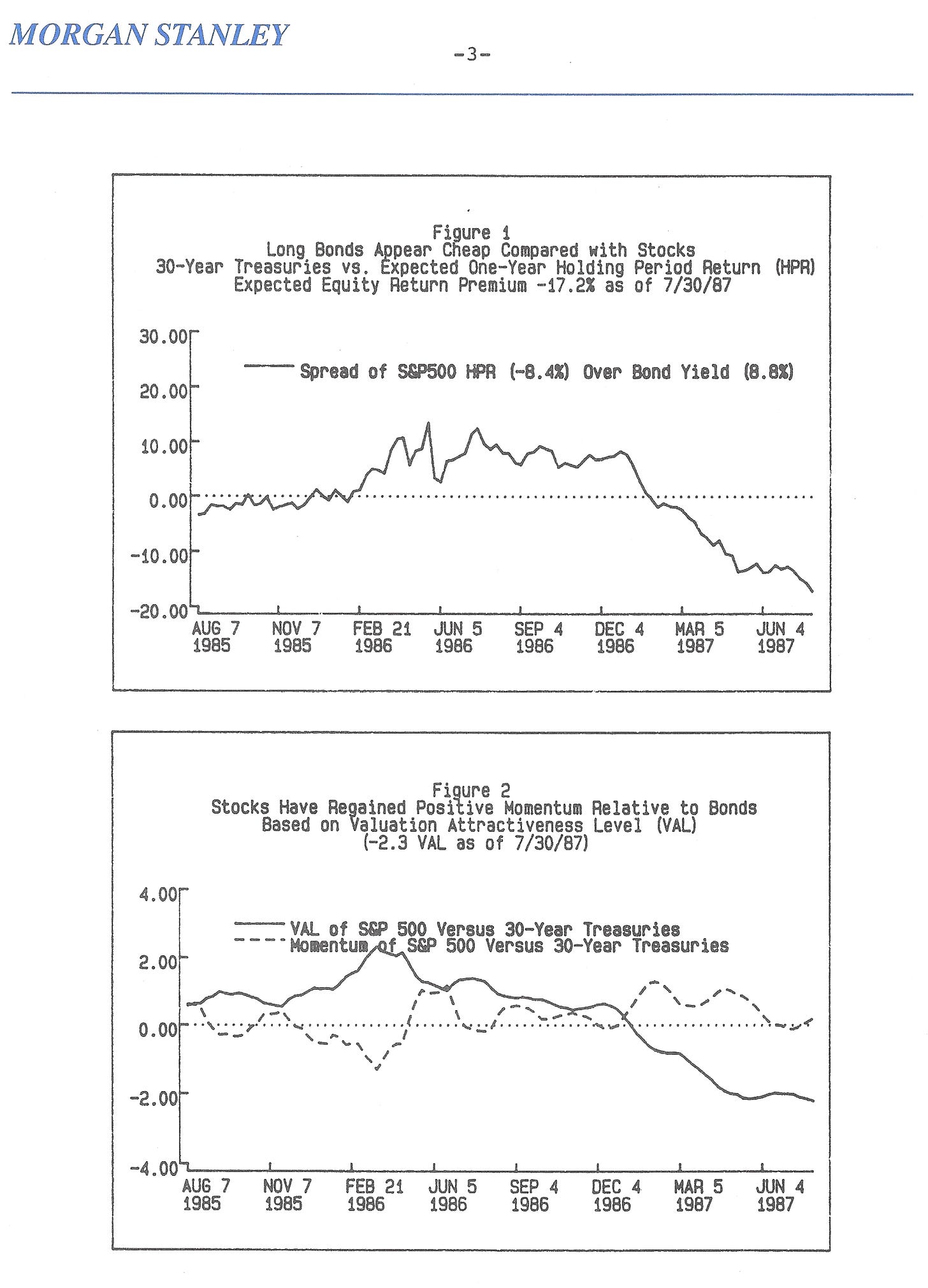

Here is a sample of my advice at the time.

In those days before the internet, I had learned enough Japanese from my Berlitz phrase book to have simple conversations with taxi drivers. I also picked up some words from listening to my English being translated when I gave a group presentation.

One of my clients in Tokyo was Daiwa. On my first visit to their building, the salesperson, Jim, led me into the beautiful marble-faced lobby and pointed to the far wall with the elevators. In those pre-911 days, there were no security procedures, so we just walked over and Jim pressed the button. One of the doors opened and Jim motioned me in. I was on the side with the floor buttons, so I pressed the one for the fifth floor. As the elevator started to rise, Jim asked me, “How did you know which floor we were going to?”

“Well, it said Kokusai (meaning International), so I figured we were going there.”

“That’s correct,” he said, “but the signs are all in Japanese, there is no English.”

I hadn’t noticed. I guess I had learned more Japanese than I realized.

Tokyo was not my favorite city, but it did have a certain charm. The business culture was very stilted, but after hours, things loosened up. On one night on the town with some of my Japanese friends, I had somehow lost track of my wallet. Back in New York, that would have meant a total loss, and the need to cancel and replace credit cards. But early the next morning, the front desk at my hotel called to tell me they had my wallet. Whoever had found it had turned it in to the police, and they knew where to find me because of the forms I had filled out upon arriving at the airport. All of my cash and credit cards were intact.

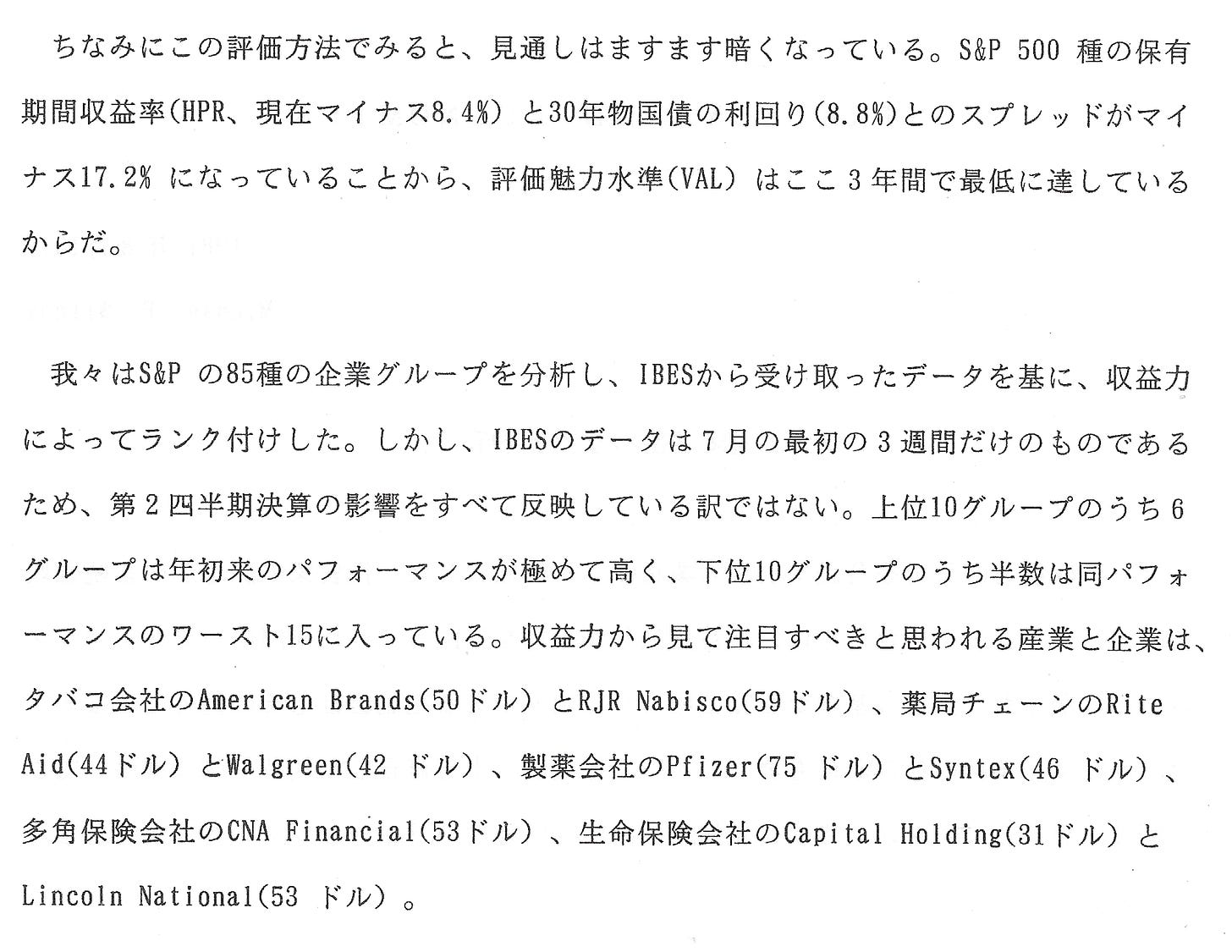

One problem in Tokyo was that there was no place to run. No matter where I was in the world, part of my daily routine was to do a 5 or 6 mile run before breakfast. I always stayed with friends or in hotels that were near parks where I could run. But that was not possible in Tokyo. The only viable spot for running was the Imperial Palace, and I usually stayed at the Imperial Hotel. There is a 5K loop around the Palace, so I did it twice.

Okay, I know you’ve been dying to see a translation, so here it is. First, in case you’re wondering why I think the current stock market is similar, just take a quick look at one very simple measure of value — dividend yield. The S&P 500 is now selling at a level where that yield is very near the low point reached in the “dot-com” bubble, and we know how that ended. I don’t know what it might take to trigger a sell-off in today’s market, but caveat emptor.